NOTES ON FLYPOSTING AND POROUS URBAN SPACE

With Special Attention To

MUSTAFA HULUSI

In her book Posters: A Global History professor Elizabeth E. Guffey (2015) writes:

In this age of immateriality, as mobile phone apps and e-mail blasts add new marketing potentials undreamed of in the […] [19th century], it may seem curious to look at posters as a distinct form. But posters’ format provides a snapshot of broader epochal transition. To be sure, posters are no longer the darlings of most modern advertisers, but they have hardly died away. Indeed, how and when they are deployed becomes all the more interesting. When Apple iPod was launched, the company chose a poster campaign, presenting silhouettes of listeners dancing against backgrounds of screaming, saturated colour, to convey the physicality and sensory depth of the iPod experience. Even – perhaps especially – in a digital age, the materiality and life of a poster can maintain a powerful hold on us.

E. E. Guffey (2015:37)

Source: http://1outdooradvertising.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/wild-posting-fly-posting.html

What makes Guffey’s survey particularly interesting to me is her in-depth consideration not of what appears on posters, what makes a good design, etc. But rather how posters and flyposting reflect and connote wider societal, cultural and political concerns.

Here we’ll be looking at flyposting through literary, filmic, social, political and personal frameworks to consider what the act of flyposting can tell us about control of and access to discursive spaces. This means considering the perceived and ‘real’ effects of physical, material sites and also assaying the various imaginaries that are attendant on or bought to light by flyposting.

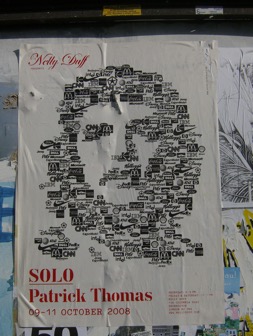

Patrick Thomas’ (2010) work Branded Che: American Investment in Cuba can be posited at one end of certain paper-based interventions on the urban environment. Thomas employs Cuban photographer Alberto Korda’s (1960) original photograph to insert an instantly recognisable figure into the streetscape. The ‘iconic’ motif captures attention through its instant recognisability and on closer inspection we can eyeball the meaning to be gleaned from Thomas’ image. Capital has finally triumphed and Che’s silhouette – shorthand for resistance to ‘the Man’ – has been populated or rather possessed by commercial global brand logos.

Branded Che: American Investment in Cuba (© 2010) by Patrick Thomas

Photo. Credit: AB

It’s not subtle but arguably submerged in cliché. It seems to lose traction because of the overused visual memes, it slips past our critical consciousness or at least the will to address the issues raised by the image do.

At the other end of the spectrum from this almost ‘smooth’ agitprop is the sort of flyposted work that dispenses with the easily visible – and easily categorised – are poster interventions that I’ll call here ‘incongruous eruptions’. Intriguing examples of work where there is no image at all. The following was photographed at Highbury and Islington (circa 2007):

Artist Unknown

Photo: AB

But there is an image, of course, the abstract mark making. A curtain of strafed daubs that record the maker’s physical gesture. But it’s the ‘conversation’ or contradiction between our commodity culture’s seemingly ever more desperate need to ‘reach an audience’, to ‘capture consumers’ attentions’ compared with this insertion of a ‘blank’, abjectly ‘pointless’ void that fascinates.

In his Monochrome Archive (1997-2015) the artist David Batchelor has been noting these sort of ‘punctuations’ (equiv. perhaps to square brackets with ellipses […] on the street), these markers of omission that draw attention to a void.

David Batchelor 53 Bow, London, 20.08.02

Source: http://www.davidbatchelor.co.uk/works/monochromes/

Batchelor talks about creating or rather locating a ‘small empty centre in an otherwise saturated field.’[1]

But not a mysterious void-in-general, rather a contingent void, a void in a place, here, today, on this particular railing in this particular street; here today, and probably gone tomorrow. A void in a place, but not in every place: these incidents are not, I noticed, distributed evenly throughout the city; they have a tendency to cluster in more overlooked and transitional environments, and are scarce in more refined and elegant districts. For me, and perhaps only for me, these bits of peripheral vision are little heroic moments […].

David Batchelor

Source: http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/bit-nothing

And similarly the work of Klara Lidén uses erasure to obscure adverts, messages, trademarks… Although the fact that she brings them back into the gallery space to exhibit introduces a further degree of separation. It’s as if she has sterilised, wiped out an instance of the spectacle and displayed it on the wall like a forlorn ‘anti-trophy’.

Klara Lidén Untitled (Poster Painting) 2010

Found Posters, blank poster paper, wheat paste.

Source: http://www.reenaspaulings.com/KL.htm

Another artist whose practice has included significant poster works sited in the urban environment for the last two decades is Mustafa Hulusi. His Expander series, dating back to the late 1990s operates, I would argue, in a very different way to, say, the Patrick Thomas’ Branded Che. Where Thomas deploys a somewhat timeworn agitprop language, what Hulusi seems to be doing, at least in part, is introducing a ‘question mark’ into the consumerist spectacle. You can google Che, and obviously you can google all of the brands from which Thomas has rendered the revolutionaries’ portrait. You can’t google Hulusi’s Expander motif. It is at once an explosion and implosion, a provocative eruption in the urban environment.

Photo: Terri Pearson

But provoking what? Here, contra to what appears to be the case with Branded Che, we are not told what to think. Nothing so emphatic is being proposed. Rather what Hulusi seems to be offering viewers or those passers-by that care to notice is a ‘tactical pointer’.[2] But again, you might ask, a pointer to what? Given that the Expander posters appeared in ‘thick’ urban space (and if you know anything of Hulusi’s wider body of work) a possible answer might be that Hulusi is questioning Capitalism’s basic assumption. That is the earth’s resources are infinite, and Capitalism is a system predicated on the never-ending exploitation of that infinite resource. But, of course, we know that the earth’s resources are in fact finite. Commercial posting is an aspect of the spectacle, a valorisation of Capital. Hulusi’s contribution to the urban environment interrupts, questions assumptions inherent in the spectacle.

But the point is Hulusi does so in an un-emphatic way. Michel Foucault purposely adopted the phrase ‘tactical pointer’ when talking about his own analyses of power because his categorical imperative was to ‘never engage in polemics’. Rather Foucault proposed (and exemplified in his writing) constant change in points of view to generate positive effects. And this, it seems to me, is what Hulusi is signalling in his graphic interventions on the street.

Here, as you might anticipate from what’s been said so far, I’m not going to dwell particularly on what’s on posters, the various elements of and debates as to design. Instead, as well as considering the importance of Hulusi’s celebration of multiple perspectives and the ‘peripheral vision’ that Batchelor and Lidén’s works point to, I want to examine references to flyposting in literature and film, consider posters as a feature of the material city and flyposting as a practice (or a job) so as to trace, explore and discuss various concerns and significances that arise…

What were habitually his final meditations?

Of some one sole unique advertisement to cause passers to stop in wonder, a poster novelty, with all extraneous accretions excluded, reduced to its simplest and most efficient terms not exceeding the span of casual vision and congruous with the velocity of modern life.

James Joyce (1922 [1969:641])

In James Joyce’s Ulysses the main character Leopold Bloom is an ad. salesman who, as we’ve just heard, philosophically dreams of the ad. to end all adverts. This, of course, is a futile task given the shifting nature and need for constant reinvention attendant on street posting or advertising in general. But this question of stripping down elements of a poster/message to its ‘simplest and most efficient terms’ to counter the ‘velocity of modern life’ is something that, French cultural theorist and urbanist, Paul Virilio has likened to a fascist strategy to stupefy and control, to bring about a mindless motivation:

“Propaganda must be made directly by words and images, not by writing,” states Goebbels […]. Reading implies time for reflection, a slowing-down that destroys the mass’s dynamic efficiency.

Paul Virilio (1977 [1986:5]) Speed and Politics Semiotext(e), NY, USA

But at the same time as positing flyposting as a fairly complex field, I also want to bear in mind a more mundane summation:

There’s nothing Romantic or daring or ‘edgy’ about it – you’re fucking sticking bits o’ paper to a fucking wall is all.

Flyposter RB (circa early 1990s)

Photo: AB

For the eight or so years I spent flyposting (or ‘on the brush’ as it’s termed) I will admit to my having an almost religious zeal for the job – I enjoyed plastering images, colour, text into the urban environment – but perhaps my friend RB is right. Flyposting, at least in part, is just a – dirty, wet, cold, sticky – shitty and sometimes dangerous occupation.

Of course, the stark dichotomy between billboard posters being a mainstay of the spectacle and its seedier aspects are brilliantly exposed in Stephen Gill’s (1999-2003) series Billboard on Billboards. The contradiction between his photographs of the grubby carnage that can often be found ‘backstage’ of billboards – the mud, car tyres, rubbish and rats – and the exotic ‘brand and adland speak’ titles he gave the images: ‘L’Oreal – “Because You’re Worth It”’ cut to the core of commodity culture’s illusory heart.

‘L’Oreal – “Because You’re Worth It’ Stephen Gill (1999 – 2003)

Source: http://media.vam.ac.uk

The flyposter (commercial or otherwise) is often an object of derision, loathing, pity or at best ambivalence. One classic ‘portrait’ of a flyposter is to be found in the Italian neo-realist film Bicycle Thieves (dir. Vittorio De Sica, 1948). What the main character of Antonio – played by Enzo Staiola – affords the director and the audience is an opportunity to tour post WWII Rome and witness a people, a city trying to resurrect itself socially, politically, economically…

Source: http://filmandphilosophy.com/2013/03/08/the-bicycle-thieves-and-italian-neorealism/

Antonio, along with the rest of Italy, is in an abject state. He needs transport to take up the offer of even this most menial of jobs. Antonio’s bike is already in hock and his wife has to pawn her precious bed linen so he can retrieve this means of transport essential to plying his trade. Although it’s not a trade proper is it? Not really recognised as such.

Flyposting in this portrayal is seen as a job at the lowest possible rung of employment. Indeed, when Antonio’s precious bicycle is stolen, part of what the film seems to be exploring is how easy it is to fall off this very thin ledge of survival, of self-sufficiency and find yourself in a position where you have no choice but to commit crime to feed yourself and your family. The moral anguish, poverty, lack of opportunity and agency is written on Antonio’s face when he is considering whether to steal someone else’s bike so he can carry on his work.

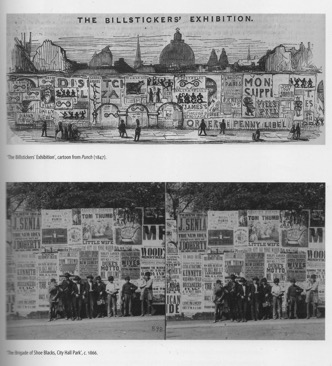

Vittorio De Sica wasn’t the first to use this sort of work – employment that hovers between legit. and illegitimate activity – to hold a mirror up to our modern societies. In the middle of the 19th century Henry Mayhew produced his exhaustive, proto-sociological study London Labour and the London Poor recording the ways in which people scraped a living in the British capital city. Coming to understand a city and the lives of its inhabitants through the jobs people do makes Mayhew an illuminating read.

‘The Billsticker’s Exhibition’, cartoon from Punch (1847) and ‘Brigade of Shoe Blacks, City Hall Park’ standing in front of an 1866 flyposting site.

Source: E. E. Guffey (2015:45)

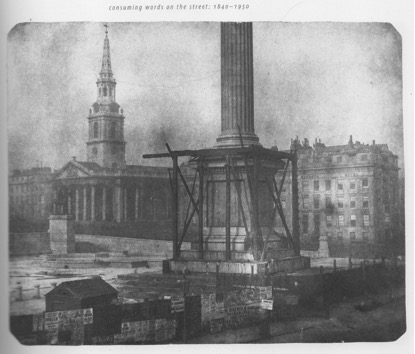

William Henry Fox Talbot, ‘Nelson’s Column under Construction, Trafalgar Square, London, April 1844’.

Source: E. E. Guffey (2015:55)

Through observation and interviews, Mayhew effects a taxonomy of ‘Those who obtain their living in the streets of the metropolis’ (1851-2 [1985:5]). He first divides ‘street people’ into six distinct groups: Street -sellers; -buyers; -finders; -performers, artists, and showmen; -artizans, or working pedlars and finally Street-labourers. It is in this last division, amongst the scavengers, nightmen, flushermen, crossing sweepers; the turn-cocks and lamplighters; street servants such as horse holders, street-porters and shoe blacks that Mayhew locates:

The street-advertisers – viz., the bill-stickers, bill-deliverers, boardmen, men to advertising vans, and wall and pavement stencillers.

Source: H. Mayhew (1851-2 [1985:8])

It’s the range of characters and activities witnessed and recorded by Mayhew that reminds us what a teeming, energetic, chaotic, sometimes desperate, more and less fluid place London was when it was the ‘most important capital in the world’.

So many of these roles, which grew out of necessity in the liminal space between ‘criminal’ and ‘legitimate’ activity over time have evolved into bona fide modes of employment. You no longer see ‘dealers in dogs, squirrels, birds, gold and silver fish, and tortoises’ plying their wares on the streets. These vendors grew their income, gained status, developed businesses in specific locations, that is shops and other fixed, regulated outlets.

Now we have the digital ‘street’ of the internet where, once again, there is a great swathe of commerce that seems to be a complete free for all. And ‘street’ is, of course, a flawed metaphor in the digital age. It’s more like a multi-storey, gyratory system that is continually shape-shifting due to technological innovation and new forms of usage. To briefly employ a bit of postmodern terminology, it’s rhizomatic:

A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo. The tree is filiation, but the rhizome is alliance, uniquely alliance. The tree imposes the verb “to be,” but the fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction, ‘and… and… and…’

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1980) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

Source: http://www.mahesh.org/articles/rhizomaticstudios.pdf

So, given this formulation of contemporary life – though I do have some qualms as to the implied super-mobility inherent in it, not everyone is as free an agent and/or interconnected as propaganda for the digital age might suggest – what adaptations, contortions, what ‘ruination’ has been visited on the contemporary human (and I’m including Bill Stickers in this) at the dawn of our digital age? What do we look like? Maybe the artist Isa Genzken had an idea (somewhat prophetically) along the right lines?

Isa Genzken. Spielautomat (Slot Machine), 1999-2000.

Slot machine, paper, chromogenic color prints, and tape 63 x 25 9/16 x 19 11/16″ (160 x 65 x 50 cm). Private Collection, Berlin Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin. © Isa Genzken

Source: http://rhizome.org/editorial/2014/feb/5/isa-genzken/

Although here is Hal Foster questioning Isa Genzken’s ‘portrait’ assemblage Spielautomat:

The pièce de résistance in this portraiture of the ruined self is Spielautomat (1999-2000), an actual slot machine covered with photographs of Genzken, friends, strangers, and celebrities mixed with urban scenes of streets and facades. Ever since Walter Benjamin speculated on the herky-jerky behaviour of Baudelaire in mid-nineteenth-century Paris, we have understood the modern subject to be one that must parry the shocks of the metropolitan world in order to survive, but the trope of the self as a slot machine, in which all play appears automated […] and all chance seems scripted […], is hard to accept, even as today we must also come to terms with our status as digital “dividuals” subject to algorithmic determination, whose data the National Security Administration can access in ways we never can.

Hal Foster (2015:88-89) Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency

Despite misgivings, I think we can agree that a rhizomatic rather than linear or hierarchical model is a more productive representation of contemporary life. And a de-centered self where boundaries between private and public, where inside and outside are disintegrating also pertains. As a practice I would say that flyposting has long occupied this murkier ground.

It’s the porosity of these sorts of employment that interests me. By which I mean they afford access to income generation that doesn’t necessarily rely on formal education or access to the higher echelons of ‘legitimate’ society. Where there’s muck there’s brass… If urbanism, social and governmental control slowly erode the spaces where these informal economies arise while we can see that certain standards – health, safety, law and order, etc. – might be improved I also think there develops a stasis or fixity that mitigates against opportunity and social mobility, or if not mobility then an achievement of sorts.

The great recorder of the growth, character and significance of myriad aspects of our metropolises, Walter Benjamin, writes in One Way Street about how it is no longer possible or at least it is no longer very productive to adopt a singular critical standpoint vis à vis society.[3]

Now things press too urgently […]. The ‘unclouded’ and ‘innocent’ eye has become a lie, perhaps the whole naïve mode of expression sheer incompetence. Today the most real, mercantile gaze into the heart of things is the advertisement.

He concludes the short entry titled This Space for Rent by suggesting it is not in the advert or sign itself that you will find any real insight into how we live today but rather in the, ‘fiery pool reflecting it in the asphalt.’ What I understand this to mean is that the effects of commodity culture are woven, scattered throughout the material and psychological networks created by and reflected in our modern cities.

In another of Mustafa Hulusi’s poster works, the Cypriot Olive Tree series (2013), he has reproduced enlarged, close-cropped photographic images of tree bark.

Source: garagemag.com

These portraits of ‘timeless’ texture were ‘imported’ from the island in the eastern Mediterranean and flyposted around East London. The introduction of this pre-human, pre-commercial, rural motif into the teeming city affords an incongruity that throws into sharp relief the tumult of speeding streets and sites of commerce. It’s as if the images are rebuking passers-by saying ‘What are you all doing? Get off the rat race wheel just for a moment?’ These works counter the reign of concrete, glass and steel: resistant materials that have become unquestioned through ubiquity in cities. The Cypriot Olive Tree works acts in the manner of ‘arte povera’ amidst the cities’ signature materials. These images of ancient, mottled and twisted flora encourage attentive viewers to at least consider alternative modes of being.

Flyposting here affords a platform whereby we can be reminded to at least question from time to time the apparently unstoppable march of lucrative development, unceasing commerce. The cynical may remark that the art market is the baldest, most raw model of a Capitalist economy but it’s worth saying that Hulusi doesn’t make any money from his poster works, they’re at best ‘loss leaders’. They might more productively be termed visual gifts that have the capacity to transport awareness, prompt imagination, introduce at least the possibility that life might be lived in a register other than being in thrall to Mammon. Hulusi himself has questioned whether, what with the relentless commercial colonisation of apparently every corner of the city, it is still even possible to employ the platform of flyposting to voice alternative views, share paradoxical opinion, perceptions, awareness?[4] Maybe that is the case, that there is no ‘outside’ neo-liberal society but perhaps Cypriot Olive Tree inserted into the contemporary urban environment at least proposes an amendment to the status quo and we’re in desperate need of that at the very least.

There’s something to be said for the nonconformist attitude that non-commercial flyposting and flyposters if not in truth evince but at least still signal. Most individuals would not have the stomach to justify such creative criminality in the face of peer or official policing. Okay, you could say that such people are simply upstanding, law abiding citizens who would no more put a poster on someone else’s wall without permission than they would shop-lift. But acting counter to social mores, disobeying boundaries erected by what’s considered accepted behaviour, confronting authority clearly isn’t always a negative act. Indeed, it may sometimes be a social duty.

Earlier I quoted James Joyce’s Ulysees. Joyce hailed from Dublin and Ulysees is an epic work aiming to communicate an equivalence of what it means to be an occupant of a modern metropolis. Though set in Dublin the book Joyce took many years to complete was written in Trieste, Zurich and Paris. I believe Dublin circa 1904 wasn’t a flyposting capital – when Joyce first had the idea of Ulysees – but Paris certainly was.[5]

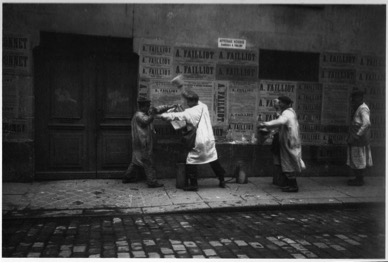

Developments in lithographic printing techniques and a relaxation in 1881 of France’s censorship and bill-posting laws saw 19th century Paris become absolutely saturated with flyposted text and images.[6] Hoardings round construction sites, disused and or unkempt buildings, fences cordoning off railway lines, alleyways, street corners… Flyposters in Paris were vying for every available urban surface, turning space into an extremely valuable commodity…

Battling bill posters: poster hangers in Paris fight over profitable street territory 1910.

Source: Elizabeth E. Guffey (2015:58)

Fighting in the street is usually an ugly scene in any era but here it’s such an apt signifier of what is at stake in the city: the value of ‘owning’ space. Residential developers and, even more so, commercial property developers to this day acquire and hoard space. Leaving buildings or plots derelict for years, sometimes decades until more favourable (financially profitable) times arrive.

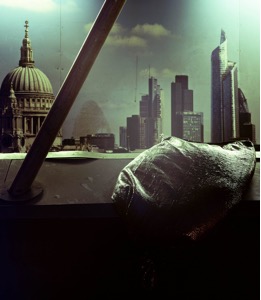

And contemporary property developments will almost always wrap their sites with branding, their self-aggrandising commercial imaginaries. There appears an increasing mania or compulsion to set the visual agenda for an urban environment they have so much invested in. I sometimes miss the time when developers were less concerned about keeping the boundaries of their sites so pristine, that ‘Considerate Construction’ we often see mentioned. I miss the time when boundary fences were platforms for other voices rather than the fierce, emphatic markers they have now more often than not become: effectively ‘sentry post guards’ for elites’ wealth and their exclusive visions. London Dust, a Rut Blees Luxemburg series of photographs examines this trend to monopolise the urban imaginary:

Vanitas (August) from the series London Dust (2012)

Photography […] is utilised by architects and property developers to create ‘computer generated visualisations’ to seduce and sell their version of the future city. These photographic renderings are displayed on a large scale in the public space, where their shiny and convincing presence oscillates between promise and despair.

Rut Blees Luxemburg[7]

James Joyce would have been aware of bill posting being a quintessentially modern urban practice. The flyposter couldn’t exist without the rise of modern cities and there’s an argument that modern cities owed, at least in part, their commercial growth and ‘success’ to the proliferation of not just flyposting but advertising and the ever faster mobility of goods, people, information…

In Ulysees we are submerged in the more and less conscious thoughts and actions of an individual in the context of a teeming modern city through sharing a day in the life of one Leopold Bloom. Bloom is a reasonable man who’s plagued by the perils of ‘contemporary’ life and Joyce’s central conceit – to restage Homer’s epic Odyssey as a ‘journey’ round Dublin – sees the author translate figures from the original Greek epic into characters Bloom encounters on one fateful day, June 16th 1904.

The Homeric character, magical and divine Circe, known for transforming men into swine – an allegory of mans’ susceptibility to lust – is recast as a madam in a brothel. The Sirens have shed their tails and in Joyce’s update have become sexy barmaids just as likely to serenade men’s foundering on the rocks of intemperance. And if the god of wind Æolus is not specifically present in Joyce’s text then its equivalent bestrides the Irish capital in the form of a newspaper editor who may ‘control the winds of opinion and other gaseous vapours.’[8]

And there’s another character in Ulysees called Hugh E. Boylan. More often referred to as Blazes Boylan. This man whom we learn toward the end of the book is the most recent in a long line to cuckold Bloom. Most recent even to the extent that Bloom is described as having to occupy the indentation Boylan has left next to Bloom’s wife Molly in the marital mattress. After brushing aside the flecked remains of some potted meat Bloom climbs in beside his sleeping missus. Blazes Boylan is a flyposter.

Given that we’ve established Joyce had a habit of ceding his characters a metaphoric aspect I wonder if Blazes Boylan who ‘smelt of some kind of drink not whisky or stout or perhaps the sweety kind of paste they stick their bills up with’ was emblematic of the corrupt and corrupting aspects of 20th century cities.

Earlier in the book, after Joyce had listed the two dozen or so men Bloom believes to have had carnal knowledge of his wife, our hapless hero Leopold ponders in greater detail as to aspects of Blazes Boylan the flyposter’s character:

What were his [Bloom’s] reflections concerning the last member of this series and late occupant of the bed?

Reflections on his vigour (a bounder), corporal proportion (a billsticker), commercial ability (a bester), impressionability (a boaster).

James Joyce (1922 [1969:652])

Bounder, bester and boaster… So, are we beginning to further piece together key character traits that belong to this literary portrait of a flyposter?

Bounder? Definition: A dishonourable man, a fortune seeker? A fortune being made from flyposting is not unknown. Bester? Comes with the (unregulated) territory: the more posters you have the more ‘ammunition’ you have to cover up rivals’ efforts. Boaster? Again, if you have the temerity to assume and maintain ownership of street spaces that don’t officially belong to you then that looks like something approaching boastful arrogance.

Of course, people come to flyposting for many different reasons. We’ve seen it as a step taken out of desperation, a no choice sort of choice. But, while admitting counter arguments, I would still say there is also potential for an agency, an independence, the ability to ‘talk’ to directly to people via a fairly straightforward, affordable means. And that can be prompted by personal, aesthetic, a political as well as an entrepreneurial intention.

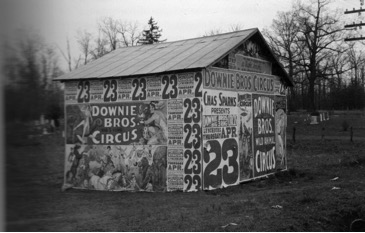

Walker Evans, ‘Posters covering a building near Lynchburg to advertise a Downie Brothers Circus’, 1936.

Source: Elizabeth E. Guffey (2015:59)

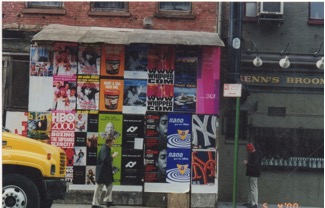

‘Wild Posting’ West Broadway/Broome St. NY (circa 2001)

That said, we are living in a time where all major cities are subject to ever more panoptic control. Pre. WW1, between the wars and certainly for some decades after WWII, cities were much less regulated places. Urbanism – that ‘science’ of architecture and planning that certainly since Baron Haussmann razed the slums of Paris and replaced them with boulevards supposedly too wide to allow barricades – urbanism has always had a more or less acknowledged political/social/ ideological agenda. But enhanced surveillance means that there are fewer and fewer spaces in cities where you can flypost.

Some – particularly owners and controllers of urban space but also everyday users of same – see this as an unmitigated benefit. There is the idea that to tolerate officially unregulated activity such as flyposting facilitates further ‘anti-social’ behaviour. In NY, US there has for some time been the ‘broken windows policy’ whereby even ‘low-level’ anti-social behaviour has in recent years lead to extremely draconian punishment. The idea being that a zero-tolerance approach towards even the smallest of infringements will put a stop to all manner of much worse criminal activity. While no one wants to feel afraid on the street, the atmosphere of fixity and prohibition that characterise the super-regulated areas of cities supports a social control that ultimately becomes internalised, affects even our most private spaces.

The more exterior space is made uniform in the contemporary city, and restricting through the length of daily trips, with its injunctive erection of signs, its nuisances, its real or imagined fears, the more one’s own space becomes smaller […]. When the public sphere no longer offers a place for political investment, men turn into ‘hermits’ in the grotto of the private living space. They hibernate in their abode, seeking to limit themselves to tiny individual pleasures. Perhaps certain ones are already dreaming in silence about other spaces for action, invention and movements. On a neighbourhood wall in June 1968, an anonymous hand wrote these words: ‘Order in the streets makes for disorder in our minds.’

Michel de Certeau et al (1990 [1998:148])

To consider a couple of more recent examples of how ‘an attack on’ or ‘the regulation of’ flyposting impacts on the personal social and psychological – and acts in the service of capital and centralised power – we can point to significant instances of this in London from the last decade.

In the Autumn of 2007 the cat and mouse game of ‘Bill Stickers’ versus Borough Councils and the Highways Agency intensified. As well as the increased action of water-jet washing down of illegal posting sites, the following sign proliferated:

STOP! Graffiti and Flyposting YOU ARE BEING FILMED

The designation and occupation of London’s Lower Lee Valley by the 2012 Olympic imaginary had a profound affect on the urban fabric and therefore on the population living in or depending on this space for a living.

Boundaries do more than control frontally, particularly in the postmodern city with its simultaneous increasing paranoia and contradictory desire for a (false) democratic and popular urban space, new kinds of boundaries have begun to emerge which seem open, seem friendly, seem attractive, yet which also control access and bodily movement. Here the tactic is not frontal exclusion but a lateral challenge to the visitor, provoking questions in the mind: am I a welcomed guest, an ambiguous transgressor, or an unwanted trespasser? Do I have the right to be here? Am I the right kind of person to be here?[9]

More and less visible boundaries were being radically redrawn. In 2007 I accompanied one particular Bill Stickers on the eve of his 65th birthday as he plied his trade around the five London boroughs of the designated Olympic site. And I want to make a quick point here, thinking about the various ways to differentiate between illegal flyposting and posting (or rather installation) of corporate, big business advertising sites that are less and less paper based.

Whilst it might be a somewhat left field argument, I wonder whether what the Bill Stickers I accompanied was doing might be viewed in terms of what Ferdinand Tönnies’ saw as the division between ‘Gemeinschaft’ and ‘Gessellschaft’?[10] (‘Community’ and ‘Society’). Large-scale corporate advertising could be said to offer the ‘mute’ exchange of the latter whilst what Bill Stickers is up to affords a much more ‘face to face’ engagement, a more porous experience.

My Bill Stickers recounted many stories that lend weight to this reading of the differences. One example is this particular Bill telling me how he originally met his now best friend (“an ex-copper”) through being out ‘on the brush’ and this individual – ostensibly representing ‘law and order’ – asking him if he had any spare boxing posters.

Again, here the immediacy and agency involved in pasting up paper posters is key. There is a sense that it is a medium open to ‘anybody’. And if this isn’t strictly true there is at least an argument that flyposting is a lot more ‘accessible’ than, say, J. C. Decaux, Primesight, Clear Channel and all, erecting billboards, vinyls, digital screen advertisements, building wraps. Clearly it’s very much less likely someone would go up to one of these companies’ operatives, strike up a conversation and try to cadge a few copies of whatever it is they are installing.

And further to the Tonnies related observation above there is a strong argument that what went on in the site(s) of the 2012 Olympic imaginary – Isle of Dogs, Greenwich Peninsula, Woolwich Arsenal, etc. – constituted an attempt to fix and neutralise the city. The hostility towards Bill Stickers was/is multi-faceted but, I think, not unrelated to modern cities’ and societies’ attitudes towards the homeless, the mentally ill… Anyone deemed to look or be acting ‘out of place’. The ‘out’ being judged locally by patrolling police and private security guards on the street liaising with CCTV controllers. Or else this designation ‘out of place’ being implicit in the on-high pronouncements relating to renewal, regeneration and the ‘opportunities’ devolving from the Olympic imaginary that undoubtedly engaged some people while at the same time emphatically excluded and continues to exclude individuals and communities.

Marc Augé’s observations as to ‘Non-Places’ or sites of supermodernity are relevant here:

In a way, the user of the non-place is always required to prove his innocence. Checks on the contract and user’s identity […] stamp the space of contemporary consumption with the sign of the non-place: it can be entered only by the innocent. […] There will be no individualisation (no right to anonymity) without identity checks.[11]

It’s not only the physical harassment and surveillance that makes for discomfort. The layout, design, the materials, the arrangement of space, architecture, street furniture and features all conspire to ‘other’ certain of the cities’ inhabitants and users.[12] Bill Stickers put it more succinctly during those Autumn 2007 outings, referring to pre-London Olympic regeneration: ‘I hate what they’re doing. Hate it!… It makes you feel like a fucking tourist.’

More recently, in 2011, some poor bloke called Mike Harding received an official letter accusing him of causing ‘urban decay’ with his ‘fly-posting’ and ordered him to remove the signs immediately or face a £1,000 fine. Mr Harding had been trying to locate his missing cat Wookie.[13]

Following Augé’s observations, in a way artists, poets, activists who use the medium of flyposting both do and don’t want anonymity.

Flyposters do want to avoid imposed order and question organising principles. Michel de Certeau’s conception of the city as a ‘Sieve Order’ helps us imagine the productive nature of complex imaginaries concerning the city.

Stories about places are makeshift things. They are composed of the world’s debris. […] These heterogeneous and even contrary elements fill the homogeneous form of the story. Things extra and other (details and excesses coming from elsewhere) insert themselves in the accepted framework, the imposed order. One thus has the very relationship between spatial practices and the constructed order. The surface of this order is everywhere punched and torn open by ellipses, drifts, and leaks of meaning: it is the sieve-order.

M. de Certeau

Source: The Practice of Everyday Life [in S. During (Ed.)] (1984 [1993:160])

In this instance the ‘spatial practice’ de Certeau is referring to is ‘walking in the city’ but his observation holds for other forms of engagement with the urban environment, its scattered fragments of multiple meanings.

De Certeau’s thoughts as to spatial and temporal porosity again owe a debt to the work of Walter Benjamin, the investigator, collector, compiler and explicator of fragments and fragmented viewpoints. One might question the word fragment as it suggests that the city was once a ‘perfect whole’ that’s been shattered and, clearly, this isn’t the case. However, a further passage from Vol. 2 of The Practice of Everyday Life wherein de Certeau and Luce Giard remind us that re-making the city is never a ‘pure’ restorative act: every time the city is disturbed or distorted by human and non-human activity and is subsequently repaired, there is a trace left of mythical past(s) (de Certeau (1994 [1998:134-143]).

It seems clear that the surfaces of cities contribute – not always in ways we can express via words – continually to this flawed process of repair and restoration. There is a continual accruing of references, more and less visible, that contributes very productive textures to our woven urban environments. The ‘sieve order’ affords potential for ‘leakage’ or, as Hulusi would have it, flyposting as a relatively inexpensive material platform leaves open the opportunity for productive eruption. A possible shift in the psychic architecture of cities, this in part informs the work of Rut Blees Luxemburg but it also would appear to be central to artists working with a quite different aesthetic vocabulary such as Laura Oldfield Ford. Her work, particularly the Savage Messiah (1995) zine, undercuts the neo-liberal ‘utopia’ and it seems apt that an early Dr D. Identify Control Dictate poster as well as Hulusi’s Expander work appears in the pages of her cut ’n’ paste social critique.

The psychic architecture of cities also features in the film High-Rise (2015 dir. Ben Wheatley) based on the novel of the same name by J.G. Ballard. This is a writer who continually forced his characters to look beyond the face value of our surroundings or rather assess how fused with, affected by aspects of the urban environment we are. So, further to examining the ‘overlit realm ruled by advertising and pseudo events, science and pornography’ as Ballard had done in the novels such as The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) and Crash (1973), writing about the film and the book High-Rise (1975) Chris Hill suggests Ballard is exploring how ‘Under imagined or liminal spaces, such as multi-storey car parks and motorway flyovers, act as metaphors for the parts of ourselves that we ignore or are unaware of.’[14]

Perhaps more than any other writer, he focussed on his characters’ physical surroundings and the effects they had on their psyches. Ballard […] was also interested in the latent content of buildings, what they represented psychologically. Or, as he once obliquely put it, “does the angle between two walls have a happy ending?” – by which he meant that we project a narrative on to external reality, that the imagination remakes the world.[15]

De Certeau talks about ‘reading’ the city but also how we are constantly ‘writing’ the city. Inscribing ourselves onto the city by the way we use it. Flyposting alerts us to the different, unexpected folds of our urban environments.

In Imagination and Time (1994) philosopher Mary Warnock says, ‘If we don’t develop imagination how can we expect people to think?’ A productive imagination helps us to pose questions about the world we live in: Who we are? How we behave? Imagination leads us to explore, express, investigate, represent and question. It’s key to ‘re-thinking’ the world, letting in different voices encourages unusual combinations of disciplines so as to rejuvenate and offer new perspectives about thinking and practice.

What’s this got to do with flyposting? Well, I’m suggesting that our urban environments are a key factor in the education of our imaginations. And what we don’t want is a wall-to-wall (street-to-street, town-to-town, city-to-city… Global) Westfield… It’s too manufactured, too brummagem, in a way too all-absorbing: a total occupation of or rather a dulling down (through obliterating bombardment) of the senses. Have you ever made sustained eye contact with someone in Westfield? Smiled at stranger there? Don’t even think about talking to one of your fellow ‘lonely crowd’ members in this sort of environment. They’ll look at you as if to say, ‘How dare you try and distract me from this hypnotic spectacle?’

In more porous and variegated, less completely managed urban spaces there are opportunities to catch glimpses of or remain open to less emphatically mediated experience. We can spy out of the corner of our eyes (and have a similarly ‘peripheral’ awareness through other senses) stuff that surprises, intrigues, charms or simply makes us stop and wonder, ask questions and construct ideas and experience afresh. David Batchelor’s blank spaces, Hulusi’s Expanders, the acts of subtraction (and revelation) caused by the NoAdDay crew… Imagination and creativity, new and productive thinking relies in part on uncertainty, on admitting risk. Untidiness helps us to question categories, rethink accepted norms. Westfield and its ilk do not admit any unscripted narratives, everything is decided: there are no blurred edges, no half perceived marginalia that might kick start a process of uncharted investigation, discovery or even awakening.

Unanticipated peripheral ‘vision’, letting in different ‘voices’, is important, it affords opportunities to construct and consider the unexpected. If Hulusi’s early Expander series references the work of Daniel Buren, continuing his questioning of the demarcation and ownership space, a more recent poster project Pomegranates (2014) introduces a geo-political critique.

At first sight these images appearing on hoardings and ‘informal’ spaces around East London, achieved a visceral assault on the senses: a shockingly brilliant visual eruption but arguably haptic and olfactory too. Today, with London’s ever more sanitised, regulated urbanism you could be forgiven for thinking we live in a cleaner, safer city. Well, perhaps we do but Hulusi’s sumptuous and cloying images of mythical putrescence suggest this isn’t everyone’s experience. Elsewhere humankind, Hulusi would argue Humanism and perhaps the Enlightenment project itself, is drowning in rottenness.

The global food industry systematically ensures 30 to 40% of all food grown in the world is thrown away as waste in order to ‘stabilize’ prices and therefore profits.

Hulusi talks persuasively of the links between outdoor advertising or more specifically posters on hoardings and elsewhere, his chosen medium and the subject of his Pomegranates project.[16] Not just in terms of waste generated but that of a geographical media being subsumed by the digitalisation of the 21st century. A shift from collective to individualised communication and also how this affords advertisers a more coercive and insidious sales tool. A necrosis bound up with Neo-Liberalism and Capitalism.

The poster as rotting fruit and vice versa is an anti-‘always switched on’ gesture, maybe melancholic like Turner’s ‘The Fighting Temeraire’, signifying the ending of one age and the beginning of another.

More specifically, gigantic and incongruous memento mori, these are Cypriot pomegranates slumping and spoiling. We can smell almost, the airless funk, witness the tragic irreversibility of decay. Hulusi cites parallels between a decadent state, an island divided where both sides are ruled by elites propped up by warring world interests, and a perpetual war being the adjunct of Capital’s myopic conceit: the old lie again, that the only way ahead is ever increased production and consumption.

Across the globe and in the streets of one of the world’s richest cities, there is the sickening stench of tax avoidance, of profits benefiting only those at the very top of the tree. Hulusi argues this image, once more a ‘gift’ but this time mouldering, references a waste of human potential, pointer to Capitalism’s boot pressed firmly on the face of the world’s poor. This might not be an obvious reading but for many passers-by in East London it’s not an uncommon experience. While economic austerity spurs on right wing politics’ fetid, dangerous and populist banalities, a moribund Socialism offers very little in the way of a credible response to the right wing prerogative: making sure the rich keep an ever tightening hold on the fruits of other people’s toil. Demagoguery peddled by the likes of Trump and Farage don’t promise much better.

With the Pomegranates, this photographic reminder of transience and fragility, I would argue Hulusi’s thinking has taken a significant turn. He is no longer, as with a previous series, singing the praises of The Joyous, Wonderful and Shining Age (2011). And, to be honest, whilst they were lush, striking works, if the title of that series didn’t contain any hint of irony I always thought they could be mistaken for utopian-realist agitprop. With Pomegranate, whilst there is still a beauty of sorts, Hulusi’s fallen fruit sits in a grey dusty soil that resembles the contents of a funereal urn. A gift of the earth has been neglected, left to fend for itself, to rot. A situation that currently chimes with peoples the world over.

Of course, now that we carry the spectacle around in our pockets a further purpose is perhaps emerging. Hulusi’s pasted street interventions are spurs to look up, take our eyes off the small screen for a moment and engage with the real world.

No one is suggesting flyposting can solve any of these issues but it seems important that there still are material platforms where questions can be raised, protest voiced. Today we might be using social media, tweeting about matters of concern but the fact of yes, using the internet but also doing something with a physical presence, putting an issue or questions before mass publics – not simply talking to the converted – affords the practice and lends the ideas proffered by this ‘ancient’ medium of communication a range of audiences and degrees of traction that might not be attendant on digital communication.

Some argue that the internet, the speed and profusion of technological innovation will facilitate an ease of surveillance, of control. And yet there is a counter argument that presently and for some time to come the technology will be developing at such an incredible pace and in unpredictable directions that the ‘digital street(s)’ are just as messy as those images I showed earlier of real messy streets, ‘written’ over, erased but leaving traces, ‘written’ over again and so ad infinitum (or until the world is all Westfield).

I’ll end by reiterating one of the main points I’m trying to communicate here, namely an argument for the social and personal, political and aesthetic value of porous urban spaces. Spaces that admit unexpected spurs to both sense(s) and intellect, this is to argue that actually these less-regulated spaces are good, if not essential for our mental wellbeing as well as social action, agency, communication, communities… Consider this obscenity:

Source: http://www.dezeen.com/2015/05/06/foster-partners-build-d3-dubai-design-district-uae/

Designed by Norman Foster’s firm Foster + Partners it is an attempt to ‘bottle’ or deliver ‘flat-packed’ the variety and unpredictability of less regulated urban space: those sites of convergence and divergence that evolve over time.

Foster’s design was apparently inspired by London’s Shoreditch and New York’s Meatpacking District being (re)conceived, created and delivered as a ‘readymade’ site. It’s called d3, it exists surrounded by desert in Dubai. Of course, this Design District has its own facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/d3Dubai/. In the short video clip posted up by Fashion Forward Dubai you will see that the transplanted ‘cultural village’ boasts a large blackboard wall whereupon passers-by are free to express themselves in coloured chalks! This makes me shudder.

Of course, not everyone swallows this ersatz monstrosity with equanimity. In the ‘i’ newspaper journalist Kate Hill interviewed Dr Gretchen Larsen of Durham University on the wisdom of planting a readymade ‘productive’ space into a cultural vacuum:

There’s more to building creative communities than just providing the space […] You need networks of people, affordable rents, policies that allow creatives time to work on their art. If there’s not already a pre-existing, organic culture in an area, then I think it will be difficult to attract genuine creativity. You can’t just whack a label on something and make it cool.

‘i’ newspaper (27.05.15)

For all its faux flux and concocted porosity, bearing in mind that ‘transgression’, or ‘mischief through the land’ is punishable by the severance of hands or hands and feet under the United Arab Emirate’s Sharia Law, I don’t think I’d risk flyposting in this location. Some people would say that’s a good thing. I hope I’ve suggested some ways in which this is not necessarily the case.

Adrian Burnham (2016)

An earlier version of this text was delivered as an Illustrated Talk at The Cass School of Art (Nov. 2015)

[1] http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/bit-nothing

[2] Michel Foucault Ref. www.protevi.com

[3] M. Bullock & M. W. Jennings (Eds) (1996 [2004:476]) Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Vol. 1 1913-1926 Harvard University Press, London

[4] Conversation with the Artist (09.11.15)

[5] R. Ellman Ulysees: A Short Story in J. Joyce (1922 [1969:705])

[6] E. E. Guffey (2015:9)

[7] Exhibition Notes for RBL’s London Dust

[8] R. Ellman Ulysees: A Short Story in J. Joyce (1922 [1969:710])

[9] Iain Borden in Steven Pile and Nigel Thrift (2000) City A-Z Routledge, London p.21

[10] Richard Sennett (1992) The Conscience of the Eye Norton, New York p.23

[11] Marc Augé (1995) Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity Verso, London p.102

[12] If you think ‘conspire’ too strong a word, for a more extended debate as to how power is wielded through the material fabric of cities see Mike Davis’ (1988 [2007])) City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles Pimlico (Random House), London p.101

[13] Andrew Levy for the Daily Mail (04.01.2011)

[14] Chris Hill in The Guardian Review (03.10.2015)

[15] Ibid.

[16] Conversation with the Artist (07.12.14)