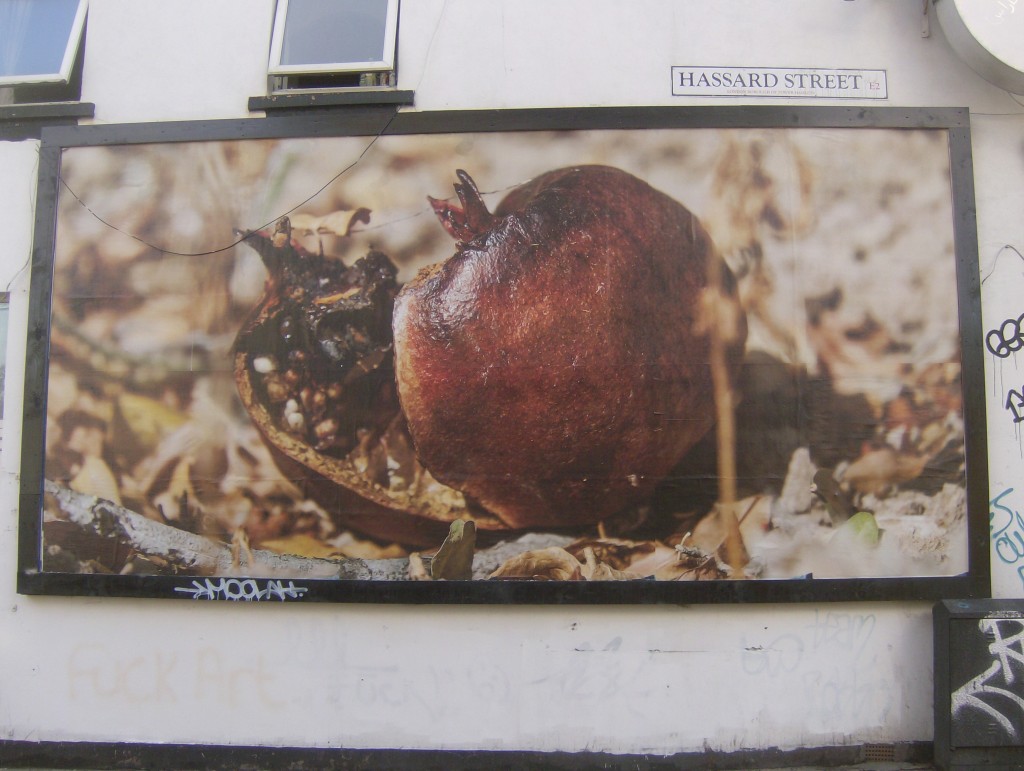

At first sight Mustafa Hulusi’s first Pomegranate (2014) series appearing on hoardings around East London, struck a nostalgic note. To feel a clump of rotting fruit caught between heel and sole, causing that awkward public leg hobble or, if really unfortunate, a slithering pratfall was once not an altogether uncommon experience. In a part of London where I grew up pedestrians had not only to contend with street traders’ discards but there was also a regular horse and livestock market with dealers trotting their beasts up and down the High Road presenting further dangers underfoot.

These days, with London’s more sanitised, regulated urbanism (and all those plastic bowls I suppose), ground-level flora is a much less common squelch. You could even be forgiven for thinking we live in a cleaner, safer city. Well, perhaps we do but Hulusi’s sumptuous and cloying images of mythical putrescence suggested this isn’t everyone’s experience. Elsewhere humankind – Hulusi would argue Humanism and perhaps the Enlightenment project itself – is drowning in rottenness.

The global food industry systematically ensures 30 to 40% of all food grown in the world is thrown away as waste in order to ‘stabilize’ prices and therefore profits.

I met the artist in Hoxton and over a suitably twattish pomegranate cocktail we chatted about his billboard project. Hulusi talks persuasively of the links between outdoor advertising or more specifically posters on hoardings, his chosen medium and also the subject of his earlier Pomegranate outing. Not just in terms of waste generated but with regard to a geographical media being subsumed by the digitalisation of the 21st century. A shift from collective to individualised communication and also how this affords advertisers a more coercive and insidious sales tool: ‘smart’ billboards spying on passers-by. A necrosis bound up with Neo-Liberalism and Capitalism.

The poster as rotting fruit and vice versa is an anti-‘always switched on’ gesture, maybe melancholic like Turner’s ‘The Fighting Temeraire’, signifying the ending of one age and the beginning of another.

More specifically, gigantic and incongruous mememto mori, these were Cypriot pomegranates slumping and spoiling. You could smell almost, the airless funk, witness the irreversibility of decay. The artist cites parallels between a decadent state, an island divided where both sides are ruled by elites propped up by warring world interests, and a perpetual war being the adjunct of Capital’s myopic conceit: that the only way ahead is ever increased production and consumption.

Across the globe and in the streets of one of the world’s richest cities, there is the sickening stench of tax avoidance, of profits benefiting only those at the very top of the tree. Hulusi argues this motif, a gift moldering, references a waste of human potential, cipher for Capitalism’s boot pressed firmly on the face of the world’s poor.

This might not have been an obvious ‘reading’ of Hulusi’s pomegranates but for many passers-by in East London and elsewhere it’s not an uncommon experience. While the economic austerity and migration panic stations persist in the wake of Ukip’s fetid, dangerous and popularist banalities and the wheels of Socialism – as peddled by new Old Labour – continue to wobble, who is there to offer a credible response to the Conservative neo-liberal diet of making sure the rich keep an ever tightening hold on the fruits of other people’s toil?

Adrian Burnham